The history of feminism comprises the narratives (

chronological

Chronology (from Latin ''chronologia'', from Ancient Greek , ''chrónos'', "time"; and , '' -logia'') is the science of arranging events in their order of occurrence in time. Consider, for example, the use of a timeline or sequence of events. ...

or thematic) of the

movements

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

and

ideologies

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied prim ...

which have aimed at

equal rights for women. While

feminists

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male poi ...

around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending on time,

culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups ...

, and country, most

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

feminist historians assert that all

movements

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

that work to obtain

women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

should be considered feminist movements, even when they did not (or do not) apply the term to themselves.

Some other historians limit the term "feminist" to the

modern feminist movement and its progeny, and use the label "

protofeminist" to describe earlier movements.

Modern Western feminist history is conventionally split into three time periods, or "waves", each with slightly different aims based on prior progress:

*

First-wave feminism

First-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity and thought that occurred during the 19th and early 20th century throughout the Western world. It focused on legal issues, primarily on securing women's right to vote. The term is often used s ...

of the 19th and early 20th centuries focused on overturning legal inequalities, particularly addressing issues of

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

*

Second-wave feminism

Second-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity that began in the early 1960s and lasted roughly two decades. It took place throughout the Western world, and aimed to increase equality for women by building on previous feminist gains.

...

(1960s–1980s) broadened debate to include

cultural inequalities,

gender norms

A gender role, also known as a sex role, is a social role encompassing a range of behaviors and attitudes that are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for a person based on that person's sex. Gender roles are usually cent ...

, and the role of women in

society

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soci ...

*

Third-wave feminism

Third-wave feminism is an iteration of the feminist movement that began in the early 1990s, prominent in the decades prior to the fourth wave. Grounded in the civil-rights advances of the second wave, Gen X and early Gen Y generations third-w ...

(1990s–2000s) refers to diverse strains of feminist activity, seen by third-wavers themselves both as a continuation of the second wave and as a response to its perceived failures

[Krolokke, Charlotte and Anne Scott Sorensen, "From Suffragettes to Grrls" in ''Gender Communication Theories and Analyses: From Silence to Performance'' (Sage, 2005).]

Although the "waves" construct has been commonly used to describe the history of feminism, the concept has also been criticized by non-White feminists for ignoring and erasing the history between the "waves", by choosing to focus solely on a few famous figures, on the perspective of a white bourgeois woman and on popular events, and for being "racist" and "colonialist."

[

]

Early feminism

People and activists who discuss or advance women's equality prior to the existence of the

feminist movement

The feminist movement (also known as the women's movement, or feminism) refers to a series of social movements and political campaigns for radical and liberal reforms on women's issues created by the inequality between men and women. Such ...

are sometimes labeled as ''protofeminist''.

Some scholars criticize this term because they believe it diminishes the importance of earlier contributions or that feminism does not have a single begin or linear history as implied by terms such as ''protofeminist'' or ''postfeminist''.

[Cott, Nancy F. "What's In a Name? The Limits of 'Social Feminism'; or, Expanding the Vocabulary of Women's History". ''Journal of American History'' 76 (December 1989): 809–829]

Around 24 centuries ago,

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, according to Elaine Hoffman Baruch, "

rguedfor the total political and sexual equality of women, advocating that they be members of his highest class, ... those who rule and fight".

Andal, a female Tamil saint, lived around the 7th or 8th century.

She is well known for writing Tiruppavai.

Andal has inspired women's groups such as Goda Mandali.

[Women's Lives, Women's Rituals in the Hindu Tradition;page 186] Her divine marriage to Vishnu is viewed by some as a feminist act, as it allowed her to avoid the regular duties of being a wife and gain autonomy.

Renaissance Feminism

Italian-French writer

Christine de Pizan (1364 – c. 1430), the author of ''

The Book of the City of Ladies

''The Book of the City of Ladies'' or ''Le Livre de la Cité des Dames'' (finished by 1405), is perhaps Christine de Pizan's most famous literary work, and it is her second work of lengthy prose. Pizan uses the vernacular French language to compo ...

'' and ''Epître au Dieu d'Amour'' (''Epistle to the God of Love'') is cited by

Simone de Beauvoir as the first woman to denounce

misogyny

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women. It is a form of sexism that is used to keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the societal roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been widely practice ...

and write about the relation of the sexes. Christine de Pizan also wrote one of the early fictional accounts of

gender transition

Gender transition is the process of changing one's gender presentation or sex characteristics to accord with one's internal sense of gender identity – the idea of what it means to be a man or a woman,Brown, M. L. & Rounsley, C. A. (1996) ''True ...

in ''

Le Livre de la mutation de fortune''.

Other early feminist writers include the 16th-century writers

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (; ; 14 September 1486 – 18 February 1535) was a German polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, theologian, and occult writer. Agrippa's '' Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' published in 1533 dre ...

,

Modesta di Pozzo di Forzi, and

Jane Anger,

and the 17th-century writers

Hannah Woolley in England,

Juana Inés de la Cruz

''Doña'' Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana, better known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (12 November 1648 – 17 April 1695) was a Mexican writer, philosopher, composer and poet of the Baroque period, and Hieronymite nun. Her contribut ...

in Mexico,

Marie Le Jars de Gournay,

Anne Bradstreet

Anne Bradstreet ( née Dudley; March 8, 1612 – September 16, 1672) was the most prominent of early English poets of North America and first writer in England's North American colonies to be published. She is the first Puritan figure in ...

,

Anna Maria van Schurman

Anna Maria van Schurman (November 5, 1607 – May 4, 1678) was a Dutch painter, engraver, poet, and scholar, who is best known for her exceptional learning and her defence of female education. She was a highly educated woman, who excelled in ...

and

François Poullain de la Barre

François Poullain de la Barre (; July 1647 – 4 May 1723) was an author, Catholic priest, and a Cartesian philosopher.

Life

François Poullain de la Barre was born on July 1647 in Paris, France, to a family with judicial nobility. He added "de ...

.

The emergence of women as true intellectuals effected change also in

Italian humanism. Cassandra Fedele was the first women to join a humanist group and achieved much despite greater constraints on women.

Renaissance defenses of women are present in a variety of literary genre and across Europe with a central claim of equality. Feminists appealed to principles that progressively lead to discourse of economic property injustice themes. Feminizing society was a way for women at this time to use literature to create interdependent and non-hierarchical systems that provided opportunities for both women and men.

Men have also played an important role in the history of defending that women are capable and able to compete equally with men, including

Antonio Cornazzano

Antonio Cornazzano (c. 1430 in Piacenza – 1484 in Ferrara) was an Italian poet, writer, biographer, and Choreography, dancing master.

Biography

In the city of Piacenza, which was then in the Duchy of Milan, Antonio Cornazzano was born probabl ...

,

Vespasiano de Bisticci, and

Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti.

Castiglione continues this trend of defending woman's moral character and that traditions are at fault for the appearance of women's inferiority. However, the critique is that there is no advocacy for social change, leaving her out of the political sphere, and abandoning her to traditional domestic roles. Although, many of them would encourage that if women were to be included in the political sphere it would be a natural consequence of their education. In addition, some of these men state that men are at fault for the lack of knowledge of intellectual women by leaving them out of historical records.

One of the most important 17th-century feminist writers in the English language was

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Margaret Lucas Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (1623 – 15 December 1673) was an English philosopher, poet, scientist, fiction writer and playwright.

Her husband, William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, was Royalist co ...

. Her knowledge was recognized by some, such as proto-feminist

Bathsua Makin

Bathsua Reginald Makin (; 1600 – c. 1675) was a teacher who contributed to the emerging criticism of woman's position in the domestic and public spheres in 17th-century England. Herself a highly educated woman, Makin was referred to as Englan ...

, who wrote that "The present Dutchess of New-Castle, by her own Genius, rather than any timely Instruction, over-tops many grave Grown-Men," and considered her a prime example of what women could become through education.

17th century

Margaret Fell's most famous work is "Women's Speaking Justified", a scripture-based argument for women's ministry, and one of the major texts on women's religious leadership in the 17th century. In this short pamphlet, Fell based her argument for equality of the sexes on one of the basic premises of

Quakerism, namely spiritual equality. Her belief was that God created all human beings, therefore both men and women were capable of not only possessing the Inner Light but also the ability to be a prophet. Fell has been described as a "feminist pioneer

18th century: the Age of Enlightenment

The

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

was characterized by secular intellectual reasoning and a flowering of philosophical writing. Many Enlightenment philosophers defended the rights of women, including

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

(1781),

Marquis de Condorcet (1790), and

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

(1792). Other important writers of the time that expressed feminist views included

Abigail Adams

Abigail Adams ( ''née'' Smith; November 22, [ O.S. November 11] 1744 – October 28, 1818) was the wife and closest advisor of John Adams, as well as the mother of John Quincy Adams. She was a founder of the United States, an ...

,

Catharine Macaulay, and

Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht.

Jeremy Bentham

The English

utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

and

classical liberal

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, econom ...

philosopher

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

said that it was the placing of women in a legally inferior position that made him choose the career of a reformist at the age of eleven, though American critic

John Neal claimed to have convinced him to take up women's rights issues during their association between 1825 and 1827. Bentham spoke for complete equality between sexes including the rights to vote and to participate in government. He opposed the asymmetrical sexual moral standards between men and women.

In his ''Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation'' (1781), Bentham strongly condemned many countries' common practice to deny women's rights due to allegedly inferior minds.

[Miriam Williford]

Bentham on the rights of Women

, ''Journal of the History of Ideas'', 1975. Bentham gave many examples of able female

regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

s.

Marquis de Condorcet

Nicolas de Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French philosopher and mathematician. His ideas, including support for a liberal economy, free and equal pu ...

was a mathematician, classical liberal politician, leading

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

ary, republican, and

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

an

anti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

ist. He was also a fierce defender of

human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

, including the equality of women and the

abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, unusual for the 1780s. He advocated for

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

in the new government in 1790 with ''De l'admission des femmes au droit de cité'' (''For the Admission to the Rights of Citizenship For Women'') and an article for ''Journal de la Société de 1789''.

Olympe de Gouges and a Declaration

Following de Condorcet's repeated, yet failed, appeals to the National Assembly in 1789 and 1790, Olympe de Gouges (in association with the Society of the Friends of Truth) authored and published the

Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in 1791. This was another plea for the French Revolutionary government to recognize the natural and political rights of women. De Gouges wrote the Declaration in the prose of the

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revolu ...

, almost mimicking the failure of men to include more than a half of the French population in ''egalité''. Even though the Declaration did not immediately accomplish its goals, it did set a precedent for a manner in which feminists could satirize their governments for their failures in equality, seen in documents such as ''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman'' and ''A Declaration of Sentiments''.

Wollstonecraft and ''A Vindication''

Perhaps the most cited feminist writer of the time was

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

, She identified the education and upbringing of women as creating their limited expectations based on a self-image dictated by the typically male perspective. Despite her perceived inconsistencies (Miriam Brody referred to the "Two Wollstonecrafts")

reflective of problems that had no easy answers, this book remains a foundation stone of feminist thought.

Wollstonecraft believed that both genders contributed to inequality. She took women's considerable power over men for granted, and determined that both would require education to ensure the necessary changes in social attitudes. Given her humble origins and scant education, her personal achievements speak to her own determination. Wollstonecraft attracted the mockery of

Samuel Johnson, who described her and her ilk as "Amazons of the pen". Based on his relationship with

Hester Thrale

Hester Lynch Thrale Piozzi (née Salusbury; later Piozzi; 27 January 1741 or 16 January 1740 – 2 May 1821),Contemporary records, which used the Julian calendar and the Annunciation Style of enumerating years, recorded her birth as 16 January ...

, he complained of women's encroachment onto a male territory of writing, and not their intelligence or education. For many commentators, Wollstonecraft represents the first codification of

equality feminism

Equality feminism is a subset of the overall feminism movement and more specifically of the liberal feminist tradition that focuses on the basic similarities between men and women, and whose ultimate goal is the equality of the sexes in all domai ...

, or a refusal of the

feminine role in society.

19th century

The feminine ideal

19th-century feminists reacted to cultural inequities including the pernicious, widespread acceptance of the

Victorian image of women's "proper" role and "sphere". The Victorian ideal created a dichotomy of "separate spheres" for men and women that was very clearly defined in theory, though not always in reality. In this ideology, men were to occupy the public sphere (the space of wage labor and politics) and women the private sphere (the space of home and children.) This "

feminine ideal", also called "

The Cult of Domesticity", was typified in Victorian

conduct books such as ''

Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management

''Mrs. Beeton's Book of Household Management'', also published as ''Mrs. Beeton's Cookery Book'', is an extensive guide to running a household in Victorian Britain, edited by Isabella Beeton and first published as a book in 1861. Previously p ...

'' and

Sarah Stickney Ellis's books. ''

The Angel in the House'' (1854) and ''El ángel del hogar'', bestsellers by

Coventry Patmore

Coventry Kersey Dighton Patmore (23 July 1823 – 26 November 1896) was an English poet and literary critic. He is best known for his book of poetry '' The Angel in the House'', a narrative poem about the Victorian ideal of a happy marriage.

...

and Maria del Pilar Sinués de Marco, came to symbolize the Victorian feminine ideal.

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

herself disparaged the concept of feminism, which she described in private letters as the "mad, wicked folly of 'Woman's Rights'".

Feminism in fiction

As

Jane Austen addressed women's restricted lives in the early part of the century,

Charlotte Brontë

Charlotte Brontë (, commonly ; 21 April 1816 – 31 March 1855) was an English novelist and poet, the eldest of the three Brontë sisters who survived into adulthood and whose novels became classics of English literature.

She enlisted i ...

,

Anne Brontë

Anne Brontë (, commonly ; 17 January 1820 – 28 May 1849) was an English novelist and poet, and the youngest member of the Brontë literary family.

Anne Brontë was the daughter of Maria (born Branwell) and Patrick Brontë, a poor Irish cl ...

,

Elizabeth Gaskell, and

George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

depicted women's misery and frustration. In her autobiographical novel ''

Ruth Hall'' (1854), American journalist

Fanny Fern

Fanny Fern (born Sara Payson Willis; July 9, 1811 – October 10, 1872), was an American novelist, children's writer, humorist, and newspaper columnist in the 1850s to 1870s. Her popularity has been attributed to a conversational style and sense ...

describes her own struggle to support her children as a newspaper columnist after her husband's untimely death.

Louisa May Alcott penned a strongly feminist novel, ''

A Long Fatal Love Chase'' (1866), about a young woman's attempts to flee her

bigamist

In cultures where monogamy is mandated, bigamy is the act of entering into a marriage with one person while still legally married to another. A legal or de facto separation of the couple does not alter their marital status as married persons. I ...

husband and become independent.

Male authors also recognized injustices against women. The novels of

George Meredith

George Meredith (12 February 1828 – 18 May 1909) was an English novelist and poet of the Victorian era. At first his focus was poetry, influenced by John Keats among others, but he gradually established a reputation as a novelist. '' The Ord ...

,

George Gissing

George Robert Gissing (; 22 November 1857 – 28 December 1903) was an English novelist, who published 23 novels between 1880 and 1903. His best-known works have reappeared in modern editions. They include '' The Nether World'' (1889), '' New Gr ...

, and

Thomas Hardy, and the plays of

Henrik Ibsen outlined the contemporary plight of women. Meredith's ''

Diana of the Crossways

''Diana of the Crossways'' is a novel by George Meredith which was published in 1885, based on the life of socialite and writer Caroline Norton.

Background

''Diana of the Crossways'' was first serialized in the ''Fortnightly'' in 1884, then p ...

'' (1885) is an account of

Caroline Norton's life. One critic later called Ibsen's plays "feministic propaganda".

John Neal

John Neal is remembered as America's first women's rights lecturer. Starting in 1823 and continuing at least as late as 1869,

[Sears (1978), p. 105] he used magazine articles, short stories, novels, public speaking, political organizing, and personal relationships to advance feminist issues in the United States and Great Britain, reaching the height of his influence in this field circa 1843. He declared intellectual equality between men and women, fought

coverture

Coverture (sometimes spelled couverture) was a legal doctrine in the English common law in which a married woman's legal existence was considered to be merged with that of her husband, so that she had no independent legal existence of her own. U ...

, and demanded suffrage, equal pay, and better education and working conditions for women. Neal's early feminist essays in the 1820s fill an intellectual gap between

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

,

Catharine Macaulay, and

Judith Sargent Murray and

Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".Wellman, 2004, p. 189 Held in the Wesleyan Chapel of the tow ...

-era successors like

Sarah Moore Grimké,

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and

Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850), sometimes referred to as Margaret Fuller Ossoli, was an American journalist, editor, critic, translator, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movemen ...

. As a male writer insulated from many common forms of attack against female feminist thinkers, Neal's advocacy was crucial in bringing the field back into the mainstream in England and the US.

In his essays for ''

Blackwood's Magazine

''Blackwood's Magazine'' was a British magazine and miscellany printed between 1817 and 1980. It was founded by the publisher William Blackwood and was originally called the ''Edinburgh Monthly Magazine''. The first number appeared in April 1817 ...

'' (1824-1825), Neal called for women's suffrage and "maintain

dthat women are not ''inferior'' to men, but only ''unlike'' men, in their intellectual properties" and "would have women treated like men, of common sense." In ''

The Yankee

''The Yankee'' (later retitled ''The Yankee and Boston Literary Gazette'') was one of the first cultural publications in the United States, founded and edited by John Neal (1793–1876), and published in Portland, Maine as a weekly periodical ...

'' magazine (1828–1829), he demanded economic opportunities for women, saying "We hope to see the day... when our women of all ages... will be able to maintain herself, without being obliged to marry for bread." At his most well-attended lecture titled "Rights of Women," Neal spoke before a crowd of around 3,000 people in 1843 at New York City's largest auditorium at the time, the

Broadway Tabernacle. Neal became even more prominently involved with the women's suffrage movement in his old age following the Civil War, both in

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

and nationally in the US by supporting

Elizabeth Cady Stanton's and

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

's

National Woman Suffrage Association

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed on May 15, 1869, to work for women's suffrage in the United States. Its main leaders were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was created after the women's rights movement s ...

and writing for its journal, ''

The Revolution''. Stanton and Anthony recognized his work after his death in their ''

History of Woman Suffrage

''History of Woman Suffrage'' is a book that was produced by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage and Ida Husted Harper. Published in six volumes from 1881 to 1922, it is a history of the women's suffrage movement, prima ...

.''

Marion Reid and Caroline Norton

At the outset of the 19th century, the dissenting feminist voices had little to no social influence. There was little sign of change in the political or social order, nor any evidence of a recognizable women's movement. Collective concerns began to coalesce by the end of the century, paralleling the emergence of a stiffer social model and code of conduct that

Marion Reid described as confining and repressive for women.

While the increased emphasis on feminine virtue partly stirred the call for a woman's movement, the tensions that this role caused for women plagued many early-19th-century feminists with doubt and worry, and fueled opposing views.

In

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

, Reid published her influential ''

A Plea for Woman

A, or a, is the first Letter (alphabet), letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, Latin alphabet, used in the English alphabet, modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name ...

'' in 1843, which proposed a transatlantic Western agenda for women's rights, including

voting rights for women.

Caroline Norton advocated for changes in British law. She discovered a lack of legal rights for women upon entering an abusive marriage.

The publicity generated from her appeal to Queen Victoria and related activism helped change English laws to recognize and accommodate married women and child custody issues.

Florence Nightingale and Frances Power Cobbe

While many women including Norton were wary of organized movements, their actions and words often motivated and inspired such movements. Among these was

Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during t ...

, whose conviction that women had all the potential of men but none of the opportunities impelled her storied nursing career.

At the time, her feminine virtues were emphasized over her ingenuity, an example of the

bias

Bias is a disproportionate weight ''in favor of'' or ''against'' an idea or thing, usually in a way that is closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Biases can be innate or learned. People may develop biases for or against an individual, a group, ...

against acknowledging female accomplishment in the mid-1800s.

[Popular image described in chapter 10: . Today's image described in: ]

Due to varying ideologies, feminists were not always supportive of each other's efforts.

Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau (; 12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist often seen as the first female sociologist, focusing on racism, race relations within much of her published material.Michael R. Hill (2002''Harriet Martineau: Th ...

and others dismissed Wollstonecraft's

contributions as dangerous, and deplored Norton's

candidness, but seized on the

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

campaign that Martineau had witnessed in the United States as one that should logically be applied to women. Her ''Society in America'' was pivotal: it caught the imagination of women who urged her to take up their cause.

Anna Wheeler

Anna Wheeler was influenced by

Saint Simonian

Saint-Simonianism was a French political, religious and social movement of the first half of the 19th century, inspired by the ideas of Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825).

Saint-Simon's ideas, expressed largely through a ...

socialists while working in France. She advocated for suffrage and attracted the attention of

Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation o ...

, the Conservative leader, as a dangerous radical on a par with

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

. She would later inspire early socialist and feminist advocate

William Thompson, who wrote the first work published in English to advocate full equality of rights for women, the 1825 "Appeal of One Half of the Human Race".

Feminists of previous centuries charged women's exclusion from education as the central cause for their domestic relegation and denial of social advancement, and women's 19th-century education was no better.

Frances Power Cobbe

Frances Power Cobbe (4 December 1822 – 5 April 1904) was an Anglo-Irish writer, philosopher, religious thinker, social reformer, anti-vivisection activist and leading women's suffrage campaigner. She founded a number of animal advocacy group ...

, among others, called for education reform, an issue that gained attention alongside marital and property rights, and domestic violence.

Female journalists like Martineau and Cobbe in Britain, and

Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850), sometimes referred to as Margaret Fuller Ossoli, was an American journalist, editor, critic, translator, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movemen ...

in America, were achieving journalistic employment, which placed them in a position to influence other women. Cobbe would refer to "

Woman's Rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

" not just in the abstract, but as an identifiable cause.

Ladies of Langham Place

Barbara Leigh Smith and her friends met regularly during the 1850s in London's Langham Place to discuss the united women's voice necessary for achieving reform. These "Ladies of Langham Place" included

Bessie Rayner Parkes

Elizabeth Rayner Belloc (; 16 June 1829 – 23 March 1925) was one of the most prominent English feminists and campaigners for women's rights in Victorian times and also a poet, essayist and journalist.

Early life

Bessie Rayner Parkes was b ...

and

Anna Jameson

Anna Brownell Jameson (17 May 179417 March 1860) was an Anglo-Irish art historian. Born in Ireland, she migrated to England at the age of four, becoming a well-known British writer and contributor to nineteenth-century thought on a range of su ...

. They focused on education, employment, and marital law. One of their causes became the Married Women's Property Committee of 1855. They collected thousands of signatures for legislative reform petitions, some of which were successful. Smith had also attended the 1848

Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".Wellman, 2004, p. 189 Held in the Wesleyan Chapel of the tow ...

in America.

Smith and Parkes, together and apart, wrote many articles on education and employment opportunities. In the same year as Norton, Smith summarized the legal framework for injustice in her 1854 ''A Brief Summary of the Laws of England concerning Women''. She was able to reach large numbers of women via her role in the ''

English Women's Journal

The ''English Woman's Journal'' was a periodical dealing primarily with female employment and equality issues. It was established in 1858 by Barbara Bodichon, Matilda Mary Hays and Bessie Rayner Parkes. Published monthly between March 1858 an ...

''. The response to this journal led to their creation of the

Society for Promoting the Employment of Women

The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women (SPEW) was one of the earliest British women's organisations.

The society was established in 1859 by Jessie Boucherett, Barbara Bodichon and Adelaide Anne Proctor to promote the training and emplo ...

(SPEW). Smith's Married Women's Property committee collected 26,000 signatures to change the law for all women, including those unmarried.

published her ''Enfranchisement'' in 1851, and wrote about the inequities of family law. In 1853, she married

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

, and provided him with much of the subject material for ''

The Subjection of Women

''The Subjection of Women'' is an essay by English philosopher, political economist and civil servant John Stuart Mill published in 1869, with ideas he developed jointly with his wife Harriet Taylor Mill. Mill submitted the finished manuscript ...

''.

Emily Davies

Sarah Emily Davies (22 April 1830 – 13 July 1921) was an English feminist and suffragist, and a pioneering campaigner for women's rights to university access. She is remembered above all as a co-founder and an early Mistress of Girton Colleg ...

also encountered the Langham group, and with

Elizabeth Garrett

Helen Elizabeth Garrett, commonly known as Elizabeth Garrett or Beth Garrett (June 30, 1963 – March 6, 2016), was an American professor of law and academic administrator. Between 2010 and 2015, she served as Provost and Senior Vice President ...

created SPEW branches outside London.

Educational reform

The interrelated barriers to education and employment formed the backbone of 19th-century feminist reform efforts, for instance, as described by Harriet Martineau in her 1859 ''

Edinburgh Journal

''Chambers's Edinburgh Journal'' was a weekly 16-page magazine started by William Chambers in 1832. The first edition was dated 4 February 1832, and priced at one penny. Topics included history, religion, language, and science. William was so ...

'' article, "Female Industry". These barriers did not change in conjunction with the economy. Martineau, however, remained a moderate, for practical reasons, and unlike Cobbe, did not support the emerging call for the vote.

The education reform efforts of women like Davies and the Langham group slowly made inroads.

Queen's College (1848) and

Bedford College (1849) in London began to offer some education to women from 1848. By 1862, Davies established a committee to persuade the universities to allow women to sit for the recently established Local Examinations, and achieved partial success in 1865. She published ''The Higher Education of Women'' a year later. Davies and Leigh Smith founded the first higher educational institution for women and enrolled five students. The school later became

Girton College, Cambridge

Girton College is one of the 31 constituent colleges of the University of Cambridge. The college was established in 1869 by Emily Davies and Barbara Bodichon as the first women's college in Cambridge. In 1948, it was granted full college status ...

in 1869,

Newnham College, Cambridge

Newnham College is a women's Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

The college was founded in 1871 by a group organising Lectures for Ladies, members of which included philosopher Henry Sid ...

in 1871, and

Lady Margaret Hall

Lady Margaret Hall (LMH) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, located on the banks of the River Cherwell at Norham Gardens in north Oxford and adjacent to the University Parks. The college is more formall ...

at Oxford in 1879. Bedford began to award degrees the previous year. Despite these measurable advances, few could take advantage of them and life for female students was still difficult.

In the 1883

Ilbert Bill controversy, a

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

bill that proposed Indian judicial jurisdiction to try British criminals, Bengali women in support of the bill responded by claiming that they were more educated than the English women opposed to the bill, and noted that more

Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

women had degrees than British women at the time.

As part of the continuing dialogue between British and American feminists,

Elizabeth Blackwell

Elizabeth Blackwell (3 February 182131 May 1910) was a British physician, notable as the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, and the first woman on the Medical Register of the General Medical Council for the United Ki ...

, one of the first American women to graduate in medicine (1849), lectured in Britain with Langham support. She eventually took her degree in France. Garrett's very successful 1870 campaign to run for London School Board office is another example of a how a small band of very determined women were beginning to reach positions of influence at the local government level.

Women's campaigns

Campaigns gave women opportunities to test their new political skills and to conjoin disparate social reform groups. Their successes include the campaign for the

Married Women's Property Act (passed in 1882) and the campaign to repeal the

Contagious Diseases Act

The Contagious Diseases Acts (CD Acts) were originally passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1864 (27 & 28 Vict. c. 85), with alterations and additions made in 1866 (29 & 30 Vict. c. 35) and 1869 (32 & 33 Vict. c. 96). In 1862, a com ...

s of 1864, 1866, and 1869, which united women's groups and utilitarian liberals like

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

.

Generally, women were outraged by the inherent inequity and misogyny of the legislation. For the first time, women in large numbers took up the rights of prostitutes. Prominent critics included Blackwell, Nightingale, Martineau, and Elizabeth Wolstenholme. Elizabeth Garrett, unlike her sister,

Millicent, did not support the campaign, though she later admitted that the campaign had done well.

Josephine Butler

Josephine Elizabeth Butler (' Grey; 13 April 1828 – 30 December 1906) was an English feminist and social reformer in the Victorian era. She campaigned for women's suffrage, the right of women to better education, the end of coverture ...

, already experienced in prostitution issues, a charismatic leader, and a seasoned campaigner, emerged as the natural leader of what became the

in 1869. Her work demonstrated the potential power of an organized lobby group. The association successfully argued that the Acts not only demeaned prostitutes, but all women and men by promoting a blatant sexual

double standard

A double standard is the application of different sets of principles for situations that are, in principle, the same. It is often used to describe treatment whereby one group is given more latitude than another. A double standard arises when two ...

. Butler's activities resulted in the radicalization of many moderate women. The Acts were repealed in 1886.

On a smaller scale,

Annie Besant

Annie Besant ( Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, freemason, women's rights activist, educationist, writer, orator, political party member and philanthropist.

Regarded as a champion of human f ...

campaigned for the rights of

matchgirls

The matchgirls' strike of 1888 was an industrial action by the women and teenage girls working at the Bryant & May match factory in Bow, London.

Background Match making

In the late nineteenth century, matches were made using sticks of popl ...

(female factory workers) and against the appalling conditions under which they worked in London. Her work of publicizing the difficult conditions of the workers through interviews in bi-weekly periodicals like The Link became a method for raising public concern over social issues.

19th to 21st centuries

Feminists did not recognize separate waves of feminism until the second wave was so named by journalist Martha Weinman Lear in a 1968 ''New York Times Magazine'' articl

"The Second Feminist Wave" according to

Alice Echols

Alice Echols is Professor of History, and the Barbra Streisand Chair of Contemporary Gender Studies at the University of Southern California. Retrieved March 17, 2013

Education

Echols received her bachelor's degree from Macalester College, Minne ...

. Jennifer Baumgardner reports criticism by professor

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (born September 10, 1938) is an American historian, writer, and activist, known for her 2014 book ''An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States''.

Early life and education

Born in San Antonio, Texas, in 1938 to ...

of the division into waves and the difficulty of categorizing some feminists into specific waves,

[Baumgardner, Jennifer, ''F'em!'', ''op. cit.'', p. 244.] argues that the main critics of a wave are likely to be members of the prior wave who remain vital,

and that waves are coming faster.

The "waves debate" has influenced how historians and other scholars have established the chronologies of women's political activis

First wave

The 19th- and early 20th-century feminist activity in the

English-speaking world

Speakers of English are also known as Anglophones, and the countries where English is natively spoken by the majority of the population are termed the '' Anglosphere''. Over two billion people speak English , making English the largest languag ...

that sought to win

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

, female education rights, better working conditions, and abolition of gender double standards is known as first-wave feminism. The term "first-wave" was coined retrospectively when the term ''

second-wave feminism

Second-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity that began in the early 1960s and lasted roughly two decades. It took place throughout the Western world, and aimed to increase equality for women by building on previous feminist gains.

Wh ...

'' was used to describe a newer feminist movement that fought social and cultural inequalities beyond basic political inequalities.

In the United States, feminist movement leaders campaigned for the national

abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

and

Temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

before championing women's rights. American first-wave feminism involved a wide range of women, some belonging to conservative Christian groups (such as

Frances Willard

Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard (September 28, 1839 – February 17, 1898) was an American educator, temperance reformer, and women's suffragist. Willard became the national president of Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1879 an ...

and the

Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

), others resembling the diversity and radicalism of much of

second-wave feminism

Second-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity that began in the early 1960s and lasted roughly two decades. It took place throughout the Western world, and aimed to increase equality for women by building on previous feminist gains.

Wh ...

(such as Stanton, Anthony,

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage (March 24, 1826 – March 18, 1898) was an American writer and activist. She is mainly known for her contributions to women's suffrage in the United States (i.e. the right to vote) but she also campaigned for Native Ameri ...

, and the

National Woman Suffrage Association

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed on May 15, 1869, to work for women's suffrage in the United States. Its main leaders were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was created after the women's rights movement s ...

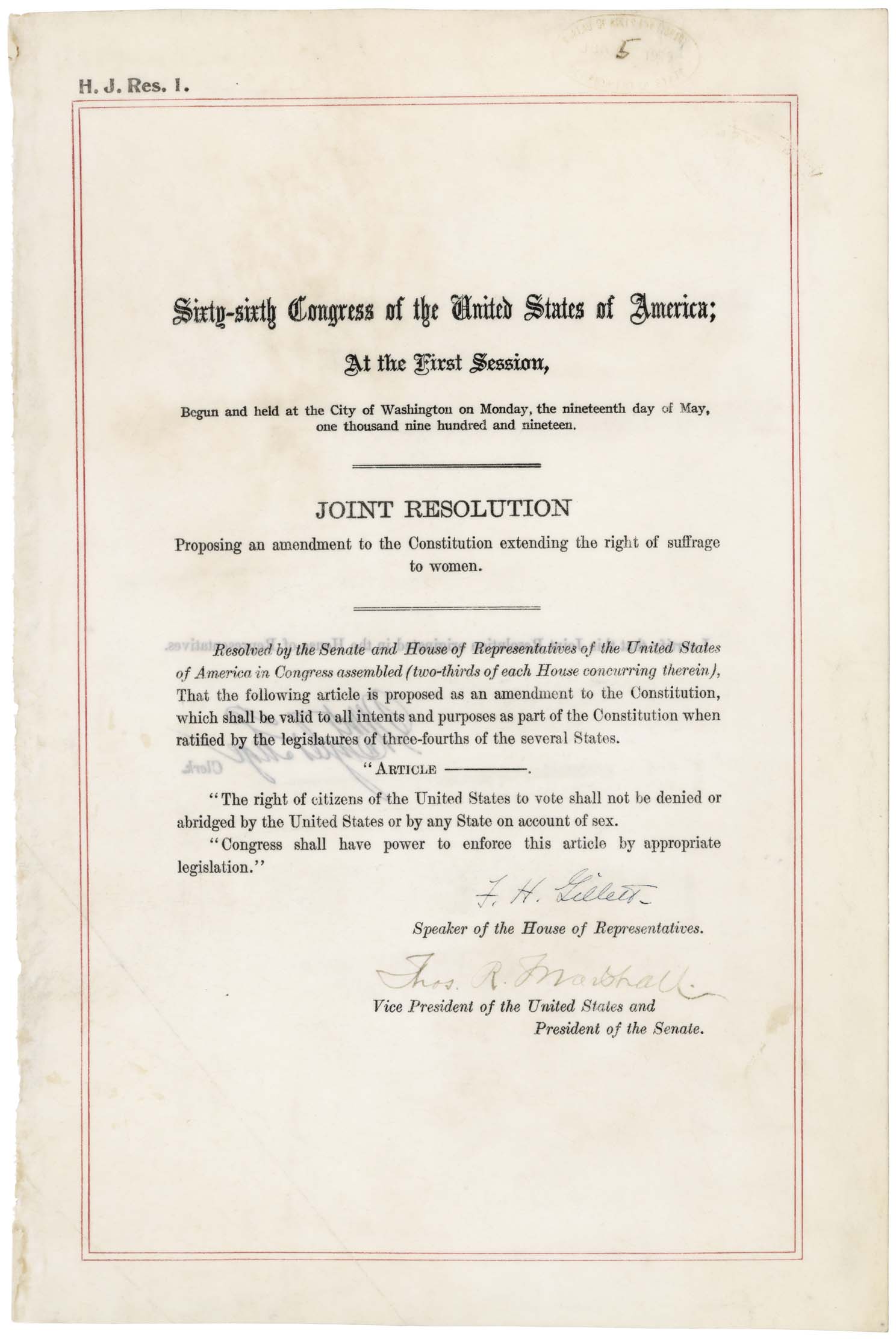

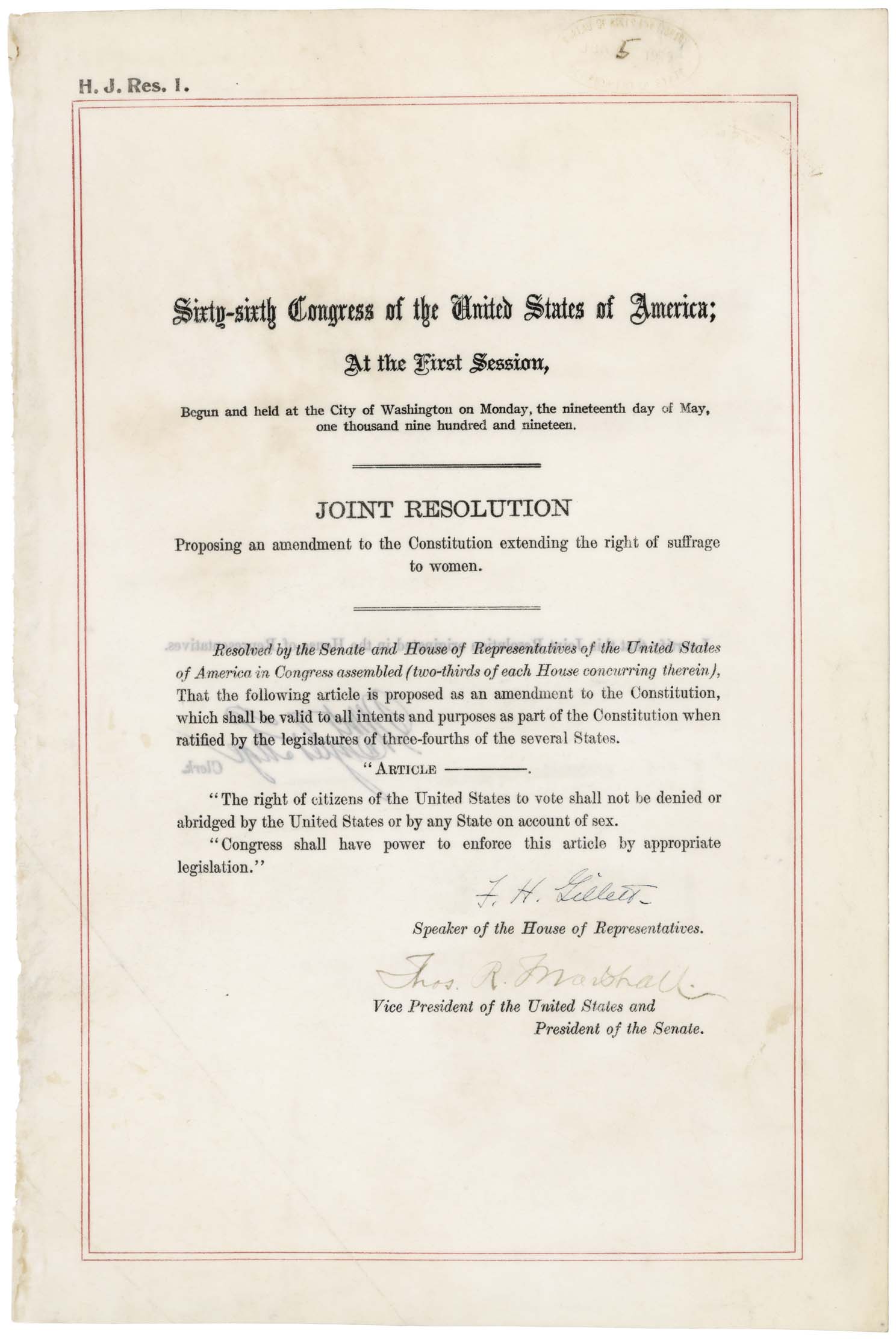

, of which Stanton was president). First-wave feminism in the United States is considered to have ended with the passage of the

Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1920), which granted women the right to vote in the United States.

Activism for the equality of women was not limited to the United States. In mid-nineteenth century Persia,

Táhirih

Táhirih (Ṭāhira) ( fa, طاهره, "The Pure One," also called Qurrat al-ʿAyn ( "Solace/Consolation of the Eyes") are both titles of Fatimah Baraghani/Umm-i Salmih (1814 or 1817 – August 16–27, 1852), an influential poet, women's rights ...

, an early member of the

Bábí Faith, was active as a poet and religious reformer. At a time when it was considered taboo for women to speak openly with men in Persia, and for non-clerics to speak about religion, she challenged the intellectuals of the age in public discourse on social and theological matters.

In 1848 she appeared before an assemblage of men without a veil and gave a speech on the rights of women, signaling a radical break with the prevailing moral order and the start of a new religious and social dispensation.

After this episode she was put under house arrest by the Persian Government until her execution by strangling at the age of 35 in August 1852.

At her execution she is reported as proclaiming "You can kill me as soon as you like, but you cannot stop the emancipation of women." The story of her life rapidly spread to European circles and she would inspire later generations of Iranian feminists.

Members of the

Bahá'í Faith recognize her as the first women's suffrage martyr and an example of fearlessness and courage in the advancement of the equality of women and men.

Louise Dittmar

Johanna Friederieke Louise Dittmar (September 7, 1807 – July 11, 1884) was a German feminist and revolutionary philosopher. She was the author of nine books, and the founding editor of the journal ''Soziale Reform''. Along with more general advo ...

campaigned for women's rights, in Germany, in the 1840s. Although slightly later in time,

Fusae Ichikawa

was a Japanese feminist, politician and a leader of the women's suffrage movement. Ichikawa was a key supporter of women's suffrage in Japan, and her activism was partially responsible for the extension of the franchise to women in 1945.

Early ...

was in the first wave of women's activists in her own country of Japan, campaigning for women's suffrage.

Mary Lee was active in the suffrage movement in South Australia, the first Australian colony to grant women the vote in 1894. In New Zealand,

Kate Sheppard

Katherine Wilson Sheppard ( Catherine Wilson Malcolm; 10 March 1848 – 13 July 1934) was the most prominent member of the women's suffrage movement in New Zealand and the country's most famous suffragist. Born in Liverpool, England, she emig ...

and

Mary Ann Müller

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

worked to achieve the vote for women by 1893.

In the United States, the antislavery campaign of the 1830s served as both a cause ideologically compatible with feminism and a blueprint for later feminist political organizing. Attempts to exclude women only strengthened their convictions.

Sarah

Sarah (born Sarai) is a biblical matriarch and prophetess, a major figure in Abrahamic religions. While different Abrahamic faiths portray her differently, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all depict her character similarly, as that of a piou ...

and

Angelina Grimké

Angelina Emily Grimké Weld (February 20, 1805 – October 26, 1879) was an American abolitionist, political activist, women's rights advocate, and supporter of the women's suffrage movement. She and her sister Sarah Moore Grimké were c ...

moved rapidly from the emancipation of slaves to the emancipation of women. The most influential feminist writer of the time was the colourful journalist

Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850), sometimes referred to as Margaret Fuller Ossoli, was an American journalist, editor, critic, translator, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movemen ...

, whose ''

Woman in the Nineteenth Century

''Woman in the Nineteenth Century'' is a book by American journalist, editor, and women's rights advocate Margaret Fuller. Originally published in July 1843 in ''The Dial'' magazine as "The Great Lawsuit. Man versus Men. Woman versus Women", it w ...

'' was published in 1845. Her dispatches from Europe for the ''

New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' helped create to synchronize the

women's rights movement

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and

Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (''née'' Coffin; January 3, 1793 – November 11, 1880) was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongs ...

met in 1840 while en route to London where they were shunned as women by the male leadership of the first

World's Anti-Slavery Convention

The World Anti-Slavery Convention met for the first time at Exeter Hall in London, on 12–23 June 1840. It was organised by the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, largely on the initiative of the English Quaker Joseph Sturge. The excl ...

. In 1848, Mott and Stanton held

a woman's rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, where a

declaration of independence for women was drafted.

Lucy Stone helped to organize the first

National Women's Rights Convention

The National Women's Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early women's rights movement in the United States. First held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, the National Women's Rights Convention ...

in 1850, a much larger event at which

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth (; born Isabella Baumfree; November 26, 1883) was an American abolitionist of New York Dutch heritage and a women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to f ...

,

Abby Kelley Foster

Abby Kelley Foster (January 15, 1811 – January 14, 1887) was an American abolitionist and radical social reformer active from the 1830s to 1870s. She became a fundraiser, lecturer and committee organizer for the influential American Anti-Sl ...

, and others spoke sparked

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

to take up the cause of women's rights. In December 1851, Sojourner Truth contributed to the feminist movement when she spoke at the Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio. She delivered her powerful "Ain't I a Woman" speech in an effort to promote women's rights by demonstrating their ability to accomplish tasks that have been traditionally associated with men.

Barbara Leigh Smith met with Mott in 1858, strengthening the link between the

transatlantic

Transatlantic, Trans-Atlantic or TransAtlantic may refer to:

Film

* Transatlantic Pictures, a film production company from 1948 to 1950

* Transatlantic Enterprises, an American production company in the late 1970s

* ''Transatlantic'' (1931 film), ...

feminist movements.

Stanton and

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage (March 24, 1826 – March 18, 1898) was an American writer and activist. She is mainly known for her contributions to women's suffrage in the United States (i.e. the right to vote) but she also campaigned for Native Ameri ...

saw

the Church as a major obstacle to women's rights, and welcomed the emerging literature on matriarchy. Both Gage and Stanton produced works on this topic, and collaborated on ''

The Woman's Bible

''The Woman's Bible'' is a two-part non-fiction book, written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and a committee of 26 women, published in 1895 and 1898 to challenge the traditional position of religious orthodoxy that woman should be subservient to man ...

''. Stanton wrote "

The Matriarchate or Mother-Age

''The'' () is a grammatical Article (grammar), article in English language, English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite ...

"

[Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. "The Matriarchate or Mother-Age", in Avery, Rachel Foster (ed.), ''Transactions of the National Council of Women of the United States''. Philadelphia, 1891.] and Gage wrote ''

Woman, Church and State'', neatly inverting

Johann Jakob Bachofen

Johann Jakob Bachofen (22 December 1815 – 25 November 1887) was a Swiss antiquarian, jurist, philologist, anthropologist, and professor for Roman law at the University of Basel from 1841 to 1845.

Bachofen is most often connected with h ...

's thesis and adding a unique

epistemological

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

perspective, the critique of objectivity and the perception of the subjective.

Stanton once observed regarding assumptions of female inferiority, "The worst feature of these assumptions is that women themselves believe them". However this attempt to replace

androcentric

Androcentrism (Ancient Greek, ἀνήρ, "man, male") is the practice, conscious or otherwise, of placing a masculine point of view at the center of one's world view, culture, and history, thereby culturally marginalizing femininity. The related a ...

(male-centered) theological tradition with a

gynocentric (female-centered) view made little headway in a women's movement dominated by religious elements; thus she and Gage were largely ignored by subsequent generations.

By 1913, Feminism (originally capitalized) was a household term in the United States. Major issues in the 1910s and 1920s included

suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

, women's partisan activism, economics and employment, sexualities and families, war and peace, and a

Constitutional amendment for equality. Both equality and difference were seen as routes to women's empowerment. Organizations at the time included the

National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NW ...

, suffrage advocacy groups such as the

National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National ...

and the

National League of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters (LWV or the League) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan political organization in the United States. Founded in 1920, its ongoing major activities include registering voters, providing voter information, and advocating for vot ...

, career associations such as the

American Association of University Women

The American Association of University Women (AAUW), officially founded in 1881, is a non-profit organization that advances equity for women and girls through advocacy, education, and research. The organization has a nationwide network of 170,000 ...

, the

National Federation of Business and Professional Women's Clubs

Business and Professional Women's Foundation (BPW) is an organization that promotes workforce development programs and workplace policies to acknowledge the needs of working women, communities, and businesses. It supports the National Federation ...

, and the

National Women's Trade Union League

The Women's Trade Union League (WTUL) (1903–1950) was a United States, U.S. organization of both working class and more well-off women to support the efforts of women to organize labor unions and to eliminate sweatshop conditions. The WTUL play ...

, war and peace groups such as the

Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) is a non-profit non-governmental organization working "to bring together women of different political views and philosophical and religious backgrounds determined to study and make kno ...

and the

International Council of Women

The International Council of Women (ICW) is a women's rights organization working across national boundaries for the common cause of advocating human rights for women. In March and April 1888, women leaders came together in Washington, D.C., with ...

, alcohol-focused groups like the

Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

and the

Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform

Pauline Morton Sabin (April 23, 1887 – December 27, 1955) was an American prohibition repeal leader and Republican party official. Born in Chicago, she was a New Yorker who founded the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR). ...

, and race- and gender-centered organizations like the

National Association of Colored Women

The National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC) is an American organization that was formed in July 1896 at the First Annual Convention of the National Federation of Afro-American Women in Washington, D.C., United States, by a merger of ...

. Leaders and theoreticians included

Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

,

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Ida B. Wells (full name: Ida Bell Wells-Barnett) (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931) was an American investigative journalist, educator, and early leader in the Civil rights movement (1896–1954), civil rights movement. She was one of the foun ...

,

Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ...

,

Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (; January 9, 1859 Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt ...

,

Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth control ...

, and

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (; née Perkins; July 3, 1860 – August 17, 1935), also known by her first married name Charlotte Perkins Stetson, was an American humanist, novelist, writer, lecturer, advocate for social reform, and eugenicist. She w ...

.

Suffrage

The women's right to vote, with its legislative representation, represented a paradigm shift where women would no longer be treated as second-class citizens without a voice. The women's suffrage campaign is the most deeply embedded campaign of the past 250 years.

At first, suffrage was treated as a lower priority. The French Revolution accelerated this, with the assertions of Condorcet and de Gouges, and the women who led the

1789 march on Versailles. In 1793, the

Society of Revolutionary Republican Women

The Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women (''Société des Citoyennes Républicaines Révolutionnaires'', ''Société des républicaines révolutionnaires'') was a female-led revolutionary organization during the French Revolution. The Soc ...

was founded, and originally included suffrage on its agenda before it was suppressed at the end of the year. As a gesture, this showed that issue was now part of the European political agenda.

German women were involved in the

Vormärz

' (; English: ''pre-March'') was a period in the history of Germany preceding the 1848 March Revolution in the states of the German Confederation. The beginning of the period is less well-defined. Some place the starting point directly after the ...

, a prelude to the

1848 revolution. In Italy, Clara Maffei,

Cristina Trivulzio Belgiojoso, and Ester Martini Currica were politically active in the events leading up to 1848. In Britain, interest in suffrage emerged from the writings of Wheeler and Thompson in the 1820s, and from Reid, Taylor, and

Anne Knight in the 1840s. While New Zealand was the first sovereign state where women won the right to vote (1893), they did not win the right to stand in elections until later. The Australian State of

South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

was the first sovereign state in the world to officially grant full suffrage to women (

in 1894).

The suffragettes

The Langham Place ladies set up a suffrage committee at an 1866 meeting at Elizabeth Garrett's home, renamed the London Society for Women's Suffrage in 1867. Soon similar committees had spread across the country, raising petitions, and working closely with John Stuart Mill. When denied outlets by establishment periodicals, feminists started their own, such as

Lydia Becker

Lydia Ernestine Becker (24 February 1827 – 18 July 1890) was a leader in the early British suffrage movement, as well as an amateur scientist with interests in biology and astronomy. She established Manchester as a centre for the suffrage mo ...

's ''

Women's Suffrage Journal

The ''Women's Suffrage Journal'' was a magazine founded by Lydia Becker and Jessie Boucherett in 1870. Initially titled the ''Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage Journal'' within a year its title was changed reflecting Becker's desir ...

'' in 1870.

Other publications included

Richard Pankhurst

Richard Marsden Pankhurst (1834 – 5 July 1898) was an English barrister and socialist who was a strong supporter of women's rights.

Early life

Richard Pankhurst was the son of Henry Francis Pankhurst (1806–1873) and Margaret Marsden (180 ...

's ''

Englishwoman's Review

''The Englishwoman's Review'' was a feminist periodical published in England between 1866 and 1910.

Until 1869 called in full ''The Englishwoman's Review: a journal of woman's work'', in 1870 (after a break in publication) it was renamed ''The ...

'' (1866). Tactical disputes were the biggest problem, and the groups' memberships fluctuated. Women considered whether men (like Mill) should be involved. As it went, Mill withdrew as the movement became more aggressive with each disappointment. The political pressure ensured debate, but year after year the movement was defeated in Parliament.

Despite this, the women accrued political experience, which translated into slow progress at the local government level. But after years of frustration, many women became increasingly radicalized. Some refused to pay taxes, and the

Pankhurst family emerged as the dominant movement influence, having also founded the

Women's Franchise League

The Women's Franchise League was a British organisation created by the suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst together with her husband Richard and others in 1889, fourteen years before the creation of the Women's Social and Political Union in 1903. The Pr ...

in 1889, which sought local election suffrage for women.

International suffrage

The Isle of Man, a UK dependency, was the first free standing jurisdiction to grant women the vote (1881), followed by the right to vote (but not to stand) in New Zealand in 1893, where

Kate Sheppard

Katherine Wilson Sheppard ( Catherine Wilson Malcolm; 10 March 1848 – 13 July 1934) was the most prominent member of the women's suffrage movement in New Zealand and the country's most famous suffragist. Born in Liverpool, England, she emig ...

had pioneered reform. Some Australian states had also granted women the vote. This included Victoria for a brief period (1863–5), South Australia (1894), and Western Australia (1899). Australian women received the vote at the Federal level in 1902, Finland in 1906, and Norway initially in 1907 (completed in 1913).

Early 20th century

In the early part of the 20th century, also known as the Edwardian era, there was a change in the way women dressed from the Victorian rigidity and complacency. Women, especially women who married a wealthy man, would often wear what we consider today, practical.

Books, articles, speeches, pictures, and papers from the period show a diverse range of themes other than political reform and suffrage discussed publicly. In the Netherlands, for instance, the main feminist issues were educational rights, rights to medical care, improved working conditions, peace, and dismantled gender double standards. Feminists identified as such with little fanfare.

Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst ('' née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Impo ...

formed the

Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and ...

(WSPU) in 1903. As she put it, they viewed votes for women no longer as "a right, but as a desperate necessity". At the state level, Australia and the United States had already granted suffrage to some women. American feminists such as

Susan B. Anthony